Chronic Illness – Taking Back Control

One of the phrases that has come to stick in our collective consciousness in recent times is the slogan for Leave.eu’s referendum campaign, “Take Back Control”. Of course, the Brexit debate is a cauldron of complexity I am certainly not aiming to discuss here. But this slogan has caused me to think about the concept of control in general and more relevantly of course, how this applies to my life with chronic, life-long illness.

It is fair to say that control is a word which gives us all some pause for thought and does elicit a certain reaction, especially in the context of our relationships with others, both at home and at work. We talk of people being ‘controlling’ or we notice our impatience (and often anger) at being ‘controlled’ by others. Perhaps more deeply, however, we seek to have a certain control over our lives – or at least feel as if we do – in a very uncertain world. There are things which we mostly have under our control (cars we drive, what we eat, read or what we study). We know – and we may dislike – the fact that there are some things over which we have almost no control (our jobs these days, climate change) where we can only exert a minimal influence through our behaviour and doing ‘our best’. There are things which we have no control over but which we choose to do regardless, making informed (or semi-informed) choices about risk and safety (flying in an aircraft, or indeed to a much lesser extent due to the known unknowns, being driven in a car or coach). There are things which we make choices to do but may in fact not have as much control over as we would like (smoking and alcohol consumption). And then the things over which we can’t possibly have any control: death is the foremost of these (excluding suicide which is far too complex to mention here); and illness.

From the time we are able to crawl around, separate from our Mummies, we have been seeking to find control over our lives and destiny in some way or another, striving for autonomy and independence. It is not an accident in life that the “terrible twos” are so called. It must be SO frustrating to be experimenting with the world and its new and exciting stimuli and reacting accordingly but not being allowed by your well-intentioned parents to do exactly what you want! The journey to adulthood is indeed perilous for all mammals and we make it with varying degrees of success given the surroundings and circumstances we encounter growing up. It is never an easy journey and most of us have to learn to accept that the world is not quite a place where we can have everything we want. Many of us, however, instead of the gradual “ideal” development where we have appropriate time and space to acclimatise to the disappointments of life, are forced far too soon, into painful and often shocking realisations that our world is not the safe and supportive place we so need it to be.

I have recently been thinking a great deal about areas of my life over which I seem to have very little control. This is an area I have become concerned with lately “thanks to” my own reconciliation process, through therapy and also as a result of the diploma course in body psychotherapy I began two years ago. I have struggled very much since I last wrote a blog to come to terms with a resurgence of severe ongoing depression and anxiety. I have always suffered from this in some way or another and to varying degrees but have usually found ways of coping, some of them not especially healthy or rational. However, recent further serious medical problems and a rapid deterioration of my lung disease have brought on a sharpening of my mental health problems. With the right help and support, I am beginning to understand the effect on me in adult life of the multiple so-called “adverse childhood experiences” that befell me before the age of 11.

Living with a chronic illness, especially throughout childhood, is one of the more difficult hands to be dealt early in life. As infants, we humans are ludicrously dependent on our parents or caregivers for safety and well-being. We control almost none of it and our brain development and ability to regulate our bodies and emotions, is dependent on high quality care from birth on. Any slight mistake of nature or nurture in those early years will be potentially disastrous for that child’s neurobiological and psychological development. Studies and wonderful developments in neuroscience research are showing that for a baby or a young child, trauma caused by any “adverse childhood experiences” (or ACEs)* – and I would include the pain and invasive nature of medical interventions the likes of which I experienced as pretty adverse and traumatic – can have long term negative psychological consequences. Any serious adverse events, especially of a repetitive nature, can cause serious behavioural and emotional problems later in life (the scale of which varies depending on the circumstances and environment). This is especially true for traumatic events during the first two years of life, which actually cause the brain to develop differently. Hardly surprising this, yet something that even now is not given enough attention yet by the established medical system.

I have noticed when speaking to other people affected by chronic illness, especially those who have come through childhood with it and have a lot of experience in hospital, that we all really struggle to cope with many aspects of life. We experience much anxiety and all share problems such as rebelling against our own disease, non-adherence to medication, difficulty at finding or keeping a job, anger at ourselves, self-destructive or risk-taking behaviours and addictions. Most notably, I find that many people with chronic illness I speak to both in person but also on Instagram, have a shared tendency to blame themselves for their illnesses and are extremely hard on themselves – especially when they are sick! It just doesn’t make sense to people who do not bear this burden of long-term illness in life – something which in itself compounds and multiplies feelings of isolation and worthlessness.

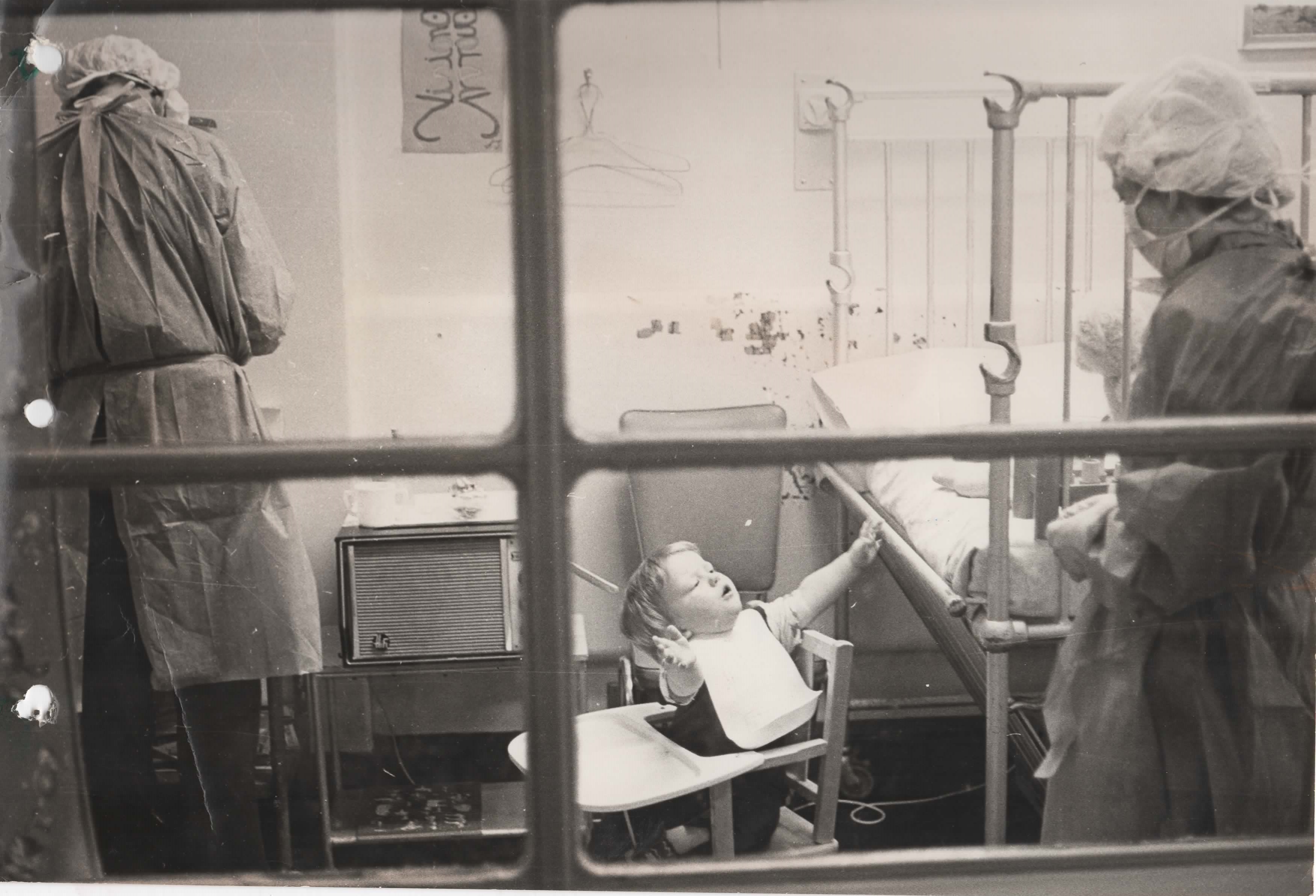

Now, it is clear that doctors performing medical procedures are not trying to cause pain and trauma. Yet, the procedures are painful and in my case, very frequent and the feeling of helplessness, fear, abandonment and all the other ingredients for traumatic stress symptoms are there in abundance. It is different now but in the Seventies, the attitude was much more austere and paternalistic with little thought being given to a patient’s emotional welfare – disastrous for children.

Much of the consequences of – and our emotional reaction to – “trauma”, (as well as what we now refer to so commonly as anxiety), can be attributed to the ancient and primal survival instinct in all of us known as the “fight, flight or freeze” response. This is initiated when we come into contact with a real (or perceived) threatening situation. All sorts of significant automatic hormonal and physical reactions occur which are governed entirely by the “autonomic nervous system” (i.e. we have no conscious control over them – heart beat, insulin production, digestion) which prepare the body to respond to immediate danger. We may need to fight, to flee or in some cases, to freeze (i.e. for an animal escaping from a predator playing dead may be the only remaining option to improve survival chances). Now, we modern humans are rarely fleeing from wild animals but life is full of stimuli that excite us in some way and need confronting or escaping from, making us angry, frightened or alarmed. We are constantly (and unconsciously) scanning our environment for safety.

Having confronted or escaped the “threat” whatever that might be (and it could be the pain of a doctor’s needle, being repeatedly screamed at by an angry parent when you are young or being cut up by the idiot driver on the way to work this morning), part of the process is to react and express emotion. Pain for example can cause us to become angry – and is a quite natural reaction once our brain has enabled us to quickly remove ourselves from the source. Yet often we are told as kids to not get angry or to stop being such a baby. Our natural reaction to express pain or anger for example, is blocked and stifled which can then negatively affect our ability to recover fully. Also, as kids we are often less able to escape from the source of our fear – again, hospital procedures come to my mind but also being repeatedly shouted at violently and told you are bad or stupid by an angry parent is another.

In my case, I had a great many early medical interventions from day one. It is only as recently as the 1960s that the medical establishment acknowledged that infants do actually feel pain (unbelievable as that may sound, it is true). Never mind the chemotherapy and lancing of painful abscesses, the simple task of drawing blood is one of the early memories that sticks in my mind: dreadful memories of being pinned to a bed in decaying windowless rooms, blinded by stark strip lighting above while several men (rarely women back then) in white coats mercilessly pierced and stabbed at my body time and again. My mother used to have to stand back and just allow it all to happen to both me and my brother and as I screamed for her to help me, she had to just watch helplessly as a bystander. She in turn would complain to her mother that she felt so guilty about suggesting they give up on my arms and try and get the blood out of my neck instead. Yet as a child, I had no ability to rationalise any of this, and was told just to “be brave” or “it’s for your own good!” The pain of it all was worsened by the fact I must have hated my mother for this betrayal and could not possibly understand the brutality I was experiencing. To make matters worse I was mostly prevented from fully expressing my pain for fear of upsetting my mum even more or being perceived as naughty or a baby or some other such nonsense that adults tend to come out with. I know I sound angry and emotional about some of this – GOOD! To me, it was genuinely torture. I used to bang my head against the steel bars of those prison like cages they call cots in which they left me alone for hours at a time.

Now, I barely feel getting stuck with canulas and needles but I remember when doctors couldn’t find veins, they would insist on digging around – up to six or eight times they would try. Nightmare. This just doesn’t happen anymore, thank heavens and I am told things have changed now in terms of what parents and caregivers are told should be their role, and how medics now approach poor children in these frightening and awful situations.

To be honest, it does get easier as an adult but the fact is I have developed a shocking disconnect from my body and some pretty awfully blurry and confused personal boundaries. When I was seven, my mum took an overdose and died at a time I most needed her. Before that she was very unwell with depression and manic anxiety making her extremely unpredictable and frankly, terrifyingly loving. As an adult I can rationalise how awful it was for her. As a baby, I also lost my brother and you would be forgiven for thinking this wouldn’t have affected me too much – I thought the same until relatively recently until I understood the burden his loss had on the family unit as a whole and how affected I would have been by his death, given we were very physically close as young brothers and how bereft my poor Mum and Dad were after he died.

In many ways, I also lost my dad the day my mother died, as the grief and shock affected him in ways we couldn’t have imagined. By the age of eleven I was being looked after by my grandparents who sent me to boarding school (spending just weekends and holidays with them) – probably the best thing that happened to me in my childhood. That says something.

I know my story is quite extreme in terms of trauma. There are many children who endure far worse things than me and to be honest, I was so lucky as I had enough care, love, support and good intention to be able to survive and live to the ripe old age of 47 (and counting) and have been able to form close interpersonal relationships. The love and care I received in spite of the traumatic circumstances was “good enough.” Yet many of us suffer terribly with what life throws at us and at our parents as we are growing up. It is my belief based on my own personal experience as well as on some very good published evidence (see below TED talk as an example), that childhood trauma plays a significant part in adult illnesses and I hope to explore this more as time goes on. But it is obvious how little control I have had over my childhood circumstances and the far-reaching effects this has had on me, and my ability to control my present. Yet it does mean I have had to slowly learn to accept what is happening in the present moment, rather than constantly being surprised at the extent and strength of my very strong emotions. I am learning techniques such as mindfulness, yoga, Qi Gong and Tai Chi to better equip me as I connect with my body again as well as coping with a lot of anxiety and depression.

But the truth is, life is really hard for everyone and we struggle to maintain any control over it – we are faced with working all the hours available for often little reward to line everyone else’s pockets, at the same time as coping with illness, divorce, redundancy and daily tales of woe and disaster on the news and in the media.

Hardly surprising therefore that the success of the Vote Leave campaign can be attributed to this notion of “taking back control” playing into the psychological weakness that affects us all daily. I don’t wish to enter into the politics of it but as far as this concept of taking back control is concerned, take it with a pinch of salt: it is a trick of enormous control in itself and it plays deliberately on people’s vulnerability and need to apportion blame. I am afraid when it comes to life, we are all puppets on a string, able to influence our destiny of course, but ultimately at the mercy of forces way beyond our control, no matter how you look at it. We all know it instinctively. It is no use seeking blame or thinking that you will be better off if (…insert own words here…). When it comes to it, we are all alone and we should focus on connecting and supporting each other, helping each other as a community to cope with our vulnerabilities, regardless of our circumstances or where we come from. In my humble opinion, it is this which will make us all happier.

* The ACE scale was drawn up as a result of research in the US and basically is a fancy way of referring to psychological trauma caused during childhood. The research relates specifically to the range of physical and social health problems encountered throughout the life span of individuals who have undergone such trauma. Technically (and curiously) it doesn’t include invasive medical interventions (or childhood bereavement) on the list but does include:

• domestic violence

• parental abandonment through separation or divorce

• a parent with a mental health condition

• being the victim of abuse (physical, sexual and/or emotional)

• being the victim of neglect (physical and emotional)

• a member of the household being in prison

• growing up in a household in which there are adults experiencing alcohol and drug use problems.

It is important to note that the ACE scale is a guideline only as each individual is so different. No two people react the same way when it comes to trauma.

For further information on ACE research, try this TED talk: https://youtu.be/95ovI J3dsNk

3 Replies to “Chronic Illness – Taking Back Control”

What a thoroughly insightful and well informed lesson for us all. It has definitely made me think about my reactions to my own and to other people’s trauma. I think the most control we have is how we react to situations – a lack of control manifests itself as fear, which in turn can come out as anger – this is definitely something I will check myself on now. Thank you.

I cried. Beautifully written, really, and as a father of a son who experienced multiple in his first few years I was able to read his story in yours. I also recognise the self-blame and shame children carry as a result of these early experiences and how that never leaves them. It’s a burden I try to help my son carry, but as you know better than I it’s hard-wired. It’s one thing to recognise intellectually the world is unsafe, but to know that in every bone and sinew of your body is a terrible load for a child. Thank you for writing this.

Simon, I am having a hard time writing this through my tears. What a beautifully written, raw, brave piece. I will need to read it again and again, there is so much to take in. As you may remember (we met at the conference a few months back) my brother has CGD and he is 48. Thank you for sharing such personal thoughts, struggles and pain . You are helping others, like me, more than you know .